Conceived and written by John Quintner and Melanie Galbraith for Arthritis and Osteoporosis WA as our contribution to the Consumer Education Sub-group, WA Pain Health.

So you have decided to board our train. We are pleased to offer you some advice along the way to help make your long journey more informative and understandable.

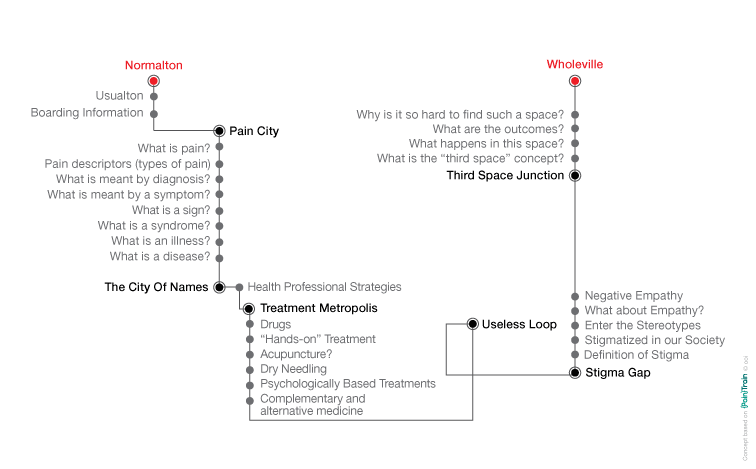

Here is the route this train will take.

Usualton (formerly known as Normalton)

You are departing from Usualton, where your daily life may have had its up and downs, but without you also having to cope with persistent pain.

Perhaps you have experienced pain on previous occasions but it has usually settled down and you have been able to carry on with, or modify, your usual life’s activities. But this time you are looking for help!

This train goes to Wholeville, stopping at all stations along the way.

Your beliefs about pain may be challenged and you may need to adopt new ways of thinking about it. We ask you to keep an open mind here!

WARNING!

Some of you may get stranded on one of the stations. Should this happen to you it will not be your fault!

BOARDING INFORMATION

When you have boarded our train and stored your baggage, please make sure you have carefully read and understood the two information sheets handed to you. They will help you make sense of your journey.

Information sheet 1. Stress/sickness response

All animals, including humans, can mount stress responses when they come into contact with stressors that they perceive as being threatening to their existence.

Note: what may be a stressor for you is not necessarily the same stressor for others. People react to stressors in different ways.

Your stress response systems are “built in” and are there to protect you. They have come down to us through a long process of evolution.

Stressors can be physical trauma (tissue damage) and/or psychological trauma (as in PTSD): both are equally capable of activating a chain of events that commences in the hypothalamus, at the base of your brain.

This chain is known as the HPA (hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal) axis. Cortisol is the key hormone released by the adrenal glands in response to stressors that you encounter.

Stress responses are designed to stop further damage to your body, to repair any damage that has occurred, and to restore its proper functioning. Fortunately for most of us they switch themselves off when they are no longer needed.

For some people their stress response systems are more easily switched on. This may be due to their previous encounters with repeated stressors, which sometimes can be traced back into their early childhood.

The stress response “switches” are controlled by genes and for reasons that are not well understood, these switches can remain in the “on” position well after the stressor is no longer present.

Then the consequences for the person can be quite distressing and involve activity in many bodily systems (e.g., endocrine, digestive, immune) resulting in widespread pain and tenderness, fatigue, sleep disturbance, problems with thinking and memory, and mood changes (anxiety and/or depression).

If this set of symptoms reflects your experience, make sure that from the outset your health professionals are made aware of this possibility, because treating a whole body system disturbance requires a whole body system approach. We call this the wHOPE (whole person engagement) Model of Care. Whatever activity you choose to undertake (e.g. listening to music, art, photography, meditation), it engages you as a whole person.

Information Sheet 2. Neuroplasticity

The good news is that your nervous system is not hard-wired, like your home electrical appliances. Rather it is “plastic” (it can make new connections), a property that allows us to learn at all stages in our life and to remember what we have learnt. It also allows us to be creative – and harnessing the brain’s plasticity by engaging in creative activities can be an important tool for managing your pain.

If you have read “The Brain that Changes Itself – Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science” by Norman Doidge, you will already know that your brain creates the world around you, including all your life experiences. As the particular experience we call “pain” is a creation of the brain it can be modified, as can all of our experiences.

How the brain is able to do these things remains a mystery but just knowing about the brain’s inherent plasticity can be a source of hope for all pain sufferers.

First stop – Pain City

As you arrive at this station, you will see a number of important signs displayed on the platform. Please study them very carefully as they offer definitions of terms that you will encounter! Our train will wait until you have read them.

Definition 1. What is pain?

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) [1979] defined “pain” for practical purposes as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”

Important: this definition severs the link between pain and tissue damage. We now accept that pain can persist long after injured tissues have healed, and that a person can have obvious tissue damage without experiencing pain (e.g. soldiers wounded in battle) or they can experience pain without evidence of tissue damage (e.g. phantom limb pain).

Food for thought:

We each live in our own world with which we connect through our bodies, but most of the time we are not aware of things happening in our bodies like our posture, our breathing, our eyelids blinking etc. But when we are experiencing pain, we suddenly become quite aware of the bodies in which we live.

However, others (such as our doctors) can perceive this same body of ours as an object for study and scientific analysis. We will be discussing the importance of this distinction.

Definition 2. Pain descriptors (types of pain)

- Nociceptive (from the Latin nocere – to harm or damage) refers to pain associated with tissue damage (noxious stimulation). Such damage can result from inflammation, poor blood supply to tissues, injury, or invasion by cancer. The nociceptive system or apparatus conveys information about tissue damage to the central nervous system (the spinal cord and brain).

Note: sometimes the information does not travel up to the brain. Messages from the brain to the spinal cord can block the incoming information from tissue damage. Serious injuries occurring on the field of battle can be sustained without the soldier feeling pain at the time. This is when the drug cabinet in the brain is opened up to release natural pain killers known as endorphins.

- Neuropathic refers to pain associated with “objective” evidence of damage or disease of the nervous system. “Objective” refers here to there being acceptable evidence of loss of nerve function, as found on clinical examination by a neurologist, and/or on electrodiagnostic testing (EMG). Example: pain associated with shingles or diabetic

- Nociplastic is a new term introduced to describe pain that is accompanied by evidence something is going wrong with the part of the nervous system that processes signals of tissue damage. The most important clue that you may be suffering from this type of pain is a hypersensitivity to non-tissue damaging stimuli – either mechanical (touch or pressure) and/or thermal (cold or hot).

In other words, the touch of your beloved is no longer pleasant, as is a cool breeze blowing upon you.

Note (1): by definition, the tissue where pain is experienced is apparently normal and there is no evidence of neurological damage.

Note (2): Nociplastic is not as yet an officially accepted pain descriptor, but it does serve the function of categorising the pain of people that does not easily fit into either of the other two categories.

Definition 3. What is meant by diagnosis?

- Diagnosis (from the Greek: to discern, distinguish, to know thoroughly): the process of identifying the disease or condition responsible for your complaints.

Our society puts considerable pressure on doctors to deliver “the diagnosis”. Woe to the patient (sufferer) in pain who comes away from a medical encounter without a “proper” diagnostic label. The important message that “pain is not to be seen on an x-ray” can too easily be forgotten. The same goes for CAT scans and MRI.

Once a diagnosis has been made, the clinician usually decides where it fits within an existing and accepted system of classification. Such a system can be thought of as a series of pigeon holes, each with its own label (i.e. category) and distinguishing properties.

Note: Two such popular systems are The International Classification of Diseases, now in its 10th revision (ICD-10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, now in its 5th revision (DSM-V).

- Differential diagnosis considers the various diseases that could possibly show themselves in a similar manner in a given

A good example is jaundice (a yellow staining of the skin due to bilirubin). It may be due to hepatitis, a blocked bile duct, or haemolytic anaemia (a rapid breakdown in red blood cells).

- Contested diagnoses are those that are based entirely upon the report of symptoms without signs (see below) or with signs that are difficult for clinicians to

Examples include “whiplash,” “repetitive strain injury,” “soft tissue injury,” “non-specific low back pain,” “fibromyalgia,” and “myofascial pain syndrome.” We suggest that the most appropriate descriptor for the pain of such poorly understood conditions is nociplastic.

Definition 4. What is meant by a symptom?

In simple terms, a symptom is “that which makes you aware of the possibility of harbouring a disease”.

Note: The term is derived from the Greek expression sumtoma, meaning an occurrence or happening, but importantly there is an implied prediction as to what might befall that person.

Definition 5. What is a sign?

A medical “sign” refers to an observable (objective) manifestation of a disease. The clinician’s role is to identify, to interpret, and to thereby give meaning to the sign.

Signs accepted as being useful in the diagnostic process have already gone through a lengthy process of being confirmed and interpreted by many clinicians. But a sign (e.g. jaundice) can also be self-observed and be given meaning by its bearer.

Definition 6. What is a syndrome?

A syndrome is a collection of symptoms and signs that tend to occur together and are connected to form a characteristic pattern. The term is derived from the Greek roots syn (meaning “together”) and dromos (meaning “a running”). Syndromes are more diagnostically substantial than symptoms and signs, but are more flexible than diseases.

Note: A syndrome can have different causes, and the same causal agent may generate different combinations of symptoms and signs.

For example, the features of carpal tunnel syndrome may be present in pregnancy, in those with diabetes, thyroid deficiency, or rheumatoid arthritis.

Definition 7.What is an illness?

The terms illness and malaise are used to describe an individual’s general perception of feeling unwell.

The description “being ill” is obviously an important means of communication. However, because it is a rather broad concept and does not seek to label, define, predict or legitimate the subjective reality that it perceives, it is of limited help in understanding what has gone wrong.

Definition 8. What is a disease?

The concept of ease comes from the old French word aise for states of comfort, pleasure, and wellbeing. Dis-ease refers to those states of being where ease is not the case.

An official definition of disease is: any deviation from or interruption of the normal structure or function of any body part, organ, or system that is manifested by a characteristic set of symptoms and signs and whose cause, pathology, and prognosis may be known or unknown.

The naming of individual diseases is a complicated process that ultimately depends upon agreement being reached amongst the majority of interested clinicians.

Note: the Internet provides an invaluable source of information on specific diseases (as well as syndromes). Look for reliable professional web sites! But beware of “non-evidence based” information!

Second Stop – The City of Names

By the time you arrive at this station you will have already learned some of the “lingo” used by those who are waiting to treat you.

Health professionals of all shapes and sizes can be found on this platform. Out in front and wearing their stethoscopes are the doctors, who are well trained to make accurate diagnoses. Naturally they will try to seek out the cause of your pain and to then treat the cause.

Well-accepted rheumatic diseases, such as gout, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis, can be diagnosed and effectively treated. Blood test(s) results and x-rays can be very helpful in making the specific diagnosis.

BUT FOR MANY PEOPLE WITH PERSISTENT PAIN A DISEASE DIAGNOSIS CANNOT BE MADE, NOR CAN ANY TISSUE SOURCE OF THEIR PAIN BE IDENTIFIED.

Many of you who are on this train will be in this situation, as was the famous writer George Orwell (Animal Farm and 1984). Let us quote from his Burmese Days:

“It is devilish to suffer from a pain that is all but nameless. Blessed are they who are stricken only with classifiable diseases! Blessed are the poor, the sick, the crossed in love, for at least other people know what is the matter with them and will listen to their belly-achings with sympathy. But who that has not suffered it understands the pains of exile?”

Some of you may have developed features of stress response activation (see above) and, as we mentioned, it is important that your treating health professionals recognise that this process is likely to have occurred. It may explain why your pain has not settled and treatment has failed to help you.

Health Professional Strategies

There are at least four strategies that can be employed by doctors (and other health professionals) who cannot arrive at an accurate diagnosis of your condition:

- To deny the reality/existence of your pain – “It’s all in your head!”

This strategy is unacceptable as it is intellectually dishonest. Unless you are lying, which is highly unlikely, why would you be on this train if you did not experience pain?

Note: you are at risk of being blamed for being in pain

- To offer a rather vague diagnosis e.g. fibromyalgia, myofascial pain, whiplash, soft tissue injury, etc.

This strategy does not advance understanding of the person’s pain. But as George Orwell observed, having a label pinned on you can be an important act of validation. However, as in these examples, sometimes the label does not help you in any way to better understand your condition.

- To order an increasing number of tests in an effort to find the tissue source of pain

Your doctor and other health professionals perceive your body as an object of scientific study and investigation. This way of proceeding is known as the biomedical model, in which you are seen as possessing a number of interconnected bodily systems and parts, each of which can be examined separately.

Note: when the biomedical model is applied to people with chronic and widespread pain, as in this strategy, it can turn out to be an expensive and fruitless exercise.

- To initiate and facilitate a “third space” engagement (discussed at STOP 6)

The strategy, which we also recommend, is not a prominent feature of our current health care system where health professionals are usually too pressed for time to actually engage with you at a meaningful level.

Third Stop – Treatment Metropolis

You will see many of the same health professionals lining this platform. But when you look more closely, you will also see a large number of CAM (complementary and alternative medicine) practitioners peddling their wares.

Without a firm medical diagnosis, all treatment (both medical and non- medical) tends to be “hit” or “miss” and as likely to be bad as it is to be good. This practice is known as “empiricism,” which means that the health professional is relying on his or her experience gained through observation.

But you should always ask your health professional – is there any scientific evidence to back up your opinion? Where there is no such evidence, proceed with caution. Quackery and fraudulent practice are still alive and well.

Note: Although there is an ever-increasing amount of information available on the Internet, as we mentioned above, finding reliable sources that are reliable can be quite difficult.

What about drugs for pain?

Drugs have been the mainstay of medical treatment and it is therefore important that you understand the concepts of Number Needed to Treat (NNT) and Number Needed to Harm (NNH) for each of them.

The NNT value for drugs used to treat specific painful conditions is derived from large clinical trials that record the number of patients who report 50% or more reduction in their pain, compared to results from those taking a placebo (e.g. a sugar pill). The lower the NNT, the better the drug.

Note: placebo (from the Latin “I will please”) can be an effective treatment too! But don’t go to your chemist and ask for a bottle of placebo!

For example, if 10 patients with a specific condition are prescribed a drug and only one of them reports 50% relief of pain compared to placebo, the NNT value for that drug is 10. This means that the other 9 patients will find the drug to be ineffective.

Continuing on the same theme, the potential for drugs to cause harmful side effects is expressed by another value – the Number Needed to Harm (NNH), again compared to placebo.

The NNH values gives you an indication of how many patients need to be treated before one of them will report a harmful side effect. The higher the NNH, the safer is the drug.

Note: It is well known that people taking placebo drugs can also report adverse events.

So how do placebos work? They appear to do this by tapping into our own powerful pain-relieving drugs (endorphins) that are produced by the brain.

NNT/NNH values are available for other forms of treatment, such as spinal injections performed to relieve pain.

USEFUL LINK: http://painhealth.csse.uwa.edu.au

Can “hands-on” treatment relieve pain?

Under “hands-on” treatment we include massage, spinal mobilization, and spinal manipulation. A short course of manual therapy (no more than 5-6 sessions) may result in immediate pain relief and provide an opportunity for you to commence a paced activity program. This should be discussed with your health professional

Note: your therapist should also be providing you with information about other pain-management strategies that you can use.

How about acupuncture?

Needle acupuncture is very popular and is said to reflect ancient Chinese Traditional Medicine practice. However, the evidence from credible reviews is that there is no single condition for which acupuncture has been found useful.

Note: A Chinese proverb states “acupuncture will work best when performed by an elderly Chinese man on an impressionable young western female,” implying that the placebo effect is all important.

What about “dry needling”?

Therapies where needles are inserted into your muscles (“dry needling”) can relieve pain by a process called “counter-irritation” – whereby causing pain with the needle provides temporary relief of existing pain! Such treatment is popular but studies have shown that it is no more effective in the medium to long term than placebo.

What psychologically based treatments are on offer?

These are usually banded together under the banner of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). They include programmes where you learn the necessary skills to cope with pain, practicing Mindfulness Meditation, and various forms of Relaxation. These therapies have all been shown to help many people in pain.

Is there a place for CAM?

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners rely heavily on the power of placebo. When their belief systems happen to coincide with yours, you are more likely to obtain pain relief. This is called “expectation bias”. Beware also of “confirmation bias,” where any improvement in your pain is put down to the particular treatment you have just received. This may well be the case, but it may also be due to a coincidental lessening of your pain.

However, many CAM practitioners offer a listening ear and this in itself can be therapeutic.

Fourth Stop – Useless Loop

Useless Loop is a stop best avoided, but this is easier said than done.

You know you have landed on this platform when you are being passed from doctor to doctor and/or your family and friends are advising you to see yet another health professional or to try their favourite folk remedy or to consult a particular CAM practitioner.

You are getting increasingly desperate, and nothing seems to be working. You will try almost anything just to get a short break from suffering your pain.

You are being offered more tests, more of the same ineffective treatment, and receiving more and more opinions. Everyone you meet seems now to be an “expert” in your pain.

You may feel that your health professionals have tried their best to help you and in some way it is your fault that they have not been successful.

To cap it off, your trusted health professional tells you – “I can’t help you any more.”

You have become what is known as a “difficult chronic pain patient,” or even a “heart-sink patient,” which many health professionals tend to avoid.

Note: you will now understand the truth of the old Roman saying: “To relieve pain is the province of the Gods”. But as you know by now, “Doctors ain’t Gods”.

Fifth Stop – Stigma Gap

Should you not have a diagnosis or have acquired one that is likely to be contested, you are at risk of being stigmatized by your family, your friends, your workmates, and even by your treating health professionals. Add in your encounters with our complex systems of personal injury compensation and you may well be in for lengthy delays on this platform.

Definition of stigma

Dating from Biblical times, a stigma was a mark placed upon the skin of a person indicating to everyone in the community that the person has been disgraced in some way or is of lowly status.

But in our society stigmata can refer to specific personal characteristics that can reduce a person’s identity “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one,” causing that person to be discredited, devalued, rejected, and socially excluded from having a voice.

Why are people in pain being stigmatized in our society?

There are a number of possible reasons but essentially it gets back to whether or not the people with whom you come into contact believe that you are in pain.

Medicine can also play an important role in the stigmatisation process. For example, as mentioned above, when you cannot provide your doctor with evidence of ongoing damage to your tissues, including the nervous system, you may not be believed.

Note: if you are in pain and applying for a Disability Support Pension or making a claim for Workers’ Compensation, the question of whether or not you are in pain is linked to another question – can you be gainfully employed?

In our society it is commonly believed that every pain will have an identifiable cause, which can be rectified. When none can be found, you are placed in the impossible situation of having to prove that you are in pain. How can anyone be expected to do this? There is no definitive test for pain – it does not show up on x-rays or on other imaging techniques.

Enter the stereotypes

It is part of our human nature to “generalize” and it makes life easier when we’re able to group similar things together. This is called “stereotyping”.

Stereotypes of people can be positive, neutral, or negative. A current example of the latter is the way in which those of different religious belief systems are categorized in segments of our society (particularly if they are labeled “asylum seekers”).

Negative stereotypes of people in chronic pain include: “heart-sink patients,” “welfare cheats,” “drug seekers,” “chronic complainers,” and “hypochondriacs”. Doctors and other health professionals are not impervious to the temptation of applying these stereotypic labels.

What about empathy?

Empathy is defined as the capacity of an observer to sense the emotions and feelings of another human being. All health professionals (including doctors) would place empathy high upon the list of their desirable attributes as healers in our society.

We have all experienced empathy at some time in our lives. When a toddler falls over and grazes their knee, we “feel” their pain as they’re crying and looking for mum to comfort them.

Recent brain imaging studies have provided a neurophysiological basis for empathy – the act of observing others who are experiencing pain triggers activation of the same neural networks that have been implicated in the direct lived experience of pain. “Mirror neurons,” as they are called, have been found in humans as well as in primates.

The concept of negative empathy.

When the observer is a health professional and the person in pain sitting in front of them is feeling that their life is so terrible they cannot bear it any longer, both of them cannot help but share the same neural networks.

This sharing of negative emotions (called the “dark” side of empathy) happens instantaneously and the natural reaction of the health professional may be to move away from the person in pain. Negative stereotypes can then suddenly appear to the health professional as quite relevant to you.

But once the health professional is able to acknowledge these emotions, dispel the stereotypes, and then to discuss these matters with the patient, a “third space” engagement becomes possible. Of course, negative empathy can flow in the opposite direction when the patient perceives “negative vibes” from the health professional. Stereotypes of doctors are also prevalent in our community.

Sixth stop – Third Space Junction

When you arrive at this station, you will not get off. Instead, you will be invited to share a cabin with a health professional that may have just boarded the train. This person actually listens to what you have to say without interrupting you and in so doing acknowledges the reality that you are experiencing pain.

You and your health professional will have understood that empathy can have two sides. You have now entered what has been called the “third space”.

What is the “third space” concept?

It is often said that Medicine is an Art and a Science. Both are important to the healing process and the “third space” is where they are able to come together. Hippocrates, the Father of Western Medicine, expressed this rather well:

“Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there also is love of humanity.” Hippocrates. Precepts, VI

It is a space which two people choose to occupy in a clinical setting and where neither one is in a position of power over the other. Mutual honesty, respect and trust are essential attributes for a successful outcome of the engagement.

One way to conceptualise the “third space” is to think of the space where children might be when they are playing happily together. Another example is to consider the space avid concertgoers are occupying when they are all listening to the same piece of music being played in the concert hall.

In simple terms, the “third space” is nothing more than the expanded space human beings occupy when they each agree to share their personal space with another human being for a specific purpose.

What happens in this space?

The role of both parties is to provide that which the other person needs to obtain. Opinions can be freely stated and information shared. Differences of opinion can be negotiated, where possible. There is no place for hostility.

Apart from obtaining pain relief, the person in pain usually has a number of other needs to be met: to be heard; to be given scientifically plausible explanations for their pain; to have their questions honestly answered; to be made aware of the treatment options available to them; to share in decision making; and to be treated with empathy and compassion.

Other needs might include self-help information, psychological and social support, quality assurance of information, roles of different health care professionals and locally available services.

The health professional wishes also to be respected and acknowledged as one who has the knowledge and experience to deliver evidence-informed advice and treatment in an honest and ethical manner.

Note for health professionals: It’s important to encourage your patient to ask questions. But have you provided them with up-to-date scientific information? Have you encouraged them to consider trying traditional methods of treatment before embarking on alternative or unconventional ones?

Only when the needs of both parties have been met, where possible, can agreement be reached on therapeutic strategies and goals.

What are the outcomes?

Outcomes depend in large part upon what each party is prepared to bring into the third space and share with the other. It is impossible to predict the outcomes of a “third space” engagement because so many factors are in simultaneous operation that can change the experience of pain. However, it is out of an engagement in this space that creative pain management strategies are given permission to emerge.

Why is it so hard to find such a space?

As you may have noticed, our health care system is not particularly friendly to people with chronic illness, and this includes many of those with persistent pain who are seeking some form of assistance.

Consultations are time-based and largely controlled by the health professional. Remuneration of the health professional is dependent upon the number of people seen in a given period of time. This situation has been referred to as “six minute sausage machine medicine”.

But through the power of social media it is now becoming possible to find health professionals who will meet your particular needs. This is not an easy task, however.

Seventh stop – Wholeville

You have finally arrived at your destination, which is so named because you have regained your “wholeness”. It is no coincidence that “healing” and “wholeness” are linked. Regaining wholeness as a person is an integral part of the healing process.

You still have pain, but by undertaking this journey you will have learned quite a lot about yourself and about those who have treated you. You will have been listened to and believed.

Here are some of the important messages that we hope you have taken on board:

- Your brain can be a powerful tool to help you manage your pain experience

- Like all of our life experiences, that of being in pain can be changed

- You are not to blame for your persistent pain

- You can experience pain without evidence of tissue damage and not experience pain when tissue damage has occurred

- Drugs (or needles) alone are not the answer

- The “third space” engagement gives you the best possible opportunity to better manage your pain

- Consider embracing the wHope model of care

Could this be your slogan? Know pain, know thyself!

Note: Other trains will be leaving from this station. You may be interested in travelling aboard one or more of them: The Creative Express, The Spirit of Mindfulness Meditation, The Exercise Xplorer, and The Pill Pullman.

Acknowledgement: We wish to thank Soula Mantalvanos for her assistance in conceiving this project, and also for providing the route map. {Pain} Train © ooi.